Achieving top-quality teaching, as determined by merit and significance, requires subject specialization from both teachers and evaluators.

Michel Scriven defines teacher evaluation as “the process of determining merit, worth or significance.” Merit refers to the quality of the work. Worth is the value of the individual to the organization, which may be greater or less than his merit.

In a previous blog post, I explored the distinction between merit and worth. Now, let’s take a deeper look at the notions of merit and significance, and who determines them. While how well a teacher teaches is her “merit”, the significance of what she is teaching is a judgement about how important it is.

Merit is often regarded as how effective one’s teaching is, and is usually what formal evaluations focus on. This will involve questions like are the students engaged or is there a reasonable balance between teacher presentation and student activity.

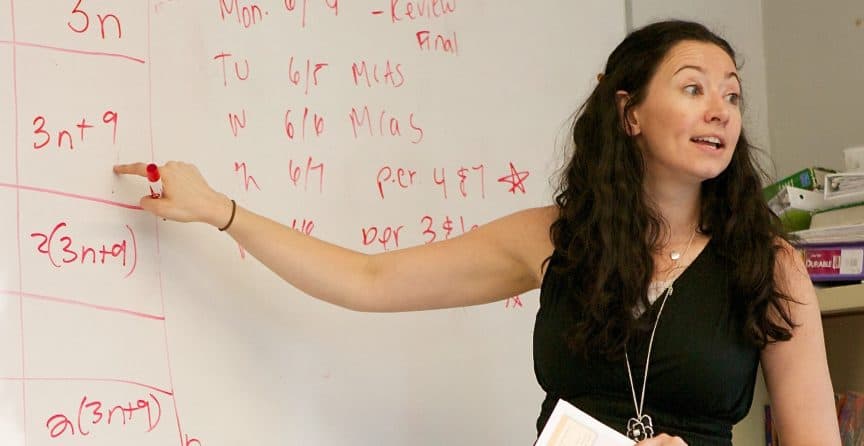

However, it is possible to use effective methods but teach material that is inaccurate or inappropriate. Therefore, a fundamental question of merit is whether the lesson is sound in its content. Are “facts” that are presented actually true? Does the mathematics teacher herself understand the fundamentals of the discipline well enough to be able to help her students make sense of it? Is history being taught so that students develop a sense of the complexity of issues? Is grammatically correct French or Spanish or Mandarin (or even English!) being modelled?

Only an evaluator with an adequate background in the subject of the lesson is able to assess these questions. Regrettably, one cannot assume that teachers are particularly knowledgeable in everything they are teaching, and an evaluator without appropriate background would not even know if students are being taught inaccurate or misleading material. Furthermore, while many teaching skills are generic and apply to whatever one is teaching, others are subject-specific. There may be better ways of helping students understand, for example, certain scientific principles than the ones the teacher is employing. An evaluator who knows little science is not in a position to make such suggestions. It is only an evaluator with expertise in both teaching and in the subject that is being taught that can make a genuine appraisal of the merit of a lesson

So what about “significance”? When I am observing in a classroom (or planning my own teaching), a question I always consider is how important is the subject of the lesson and the activities that students are assigned. In English classes, for example, if much time is being devoted to literature of questionable quality, no matter how well it is being taught, I would worry about the time and opportunity that is being wasted on matter of little value, or significance. When large bocks of time are being devoted to a project, one should always weigh whether the significance of what students are expected to learn through that activity is sufficient to warrant the time being devoted to it. In the same way that merit can only be adequately assessed by one with sufficient understanding of the subject of the lesson, significance can often also only be properly understood by one steeped in the particular discipline. When I am observing a lesson in a subject I know little about, I cannot really assess how important that particular lesson is in helping students achieve the curriculum objectives.

How important – even desirable – it is to have specialist rather than generalist teachers especially in the younger grades, is a matter of debate amongst educators. I am firmly on the side of having highly specialized teachers for even young children. While I recognize that very young children, and also some older students with certain learning difficulties, need the stability of having relatively few teachers and transitions in a day, this places a great burden on those teachers to be very broadly educated. I simply don’t believe that one can teach anything at any level really well if one knows and cares little about it. Everything else – for example, teaching skill or student relationships – being equal, there is no comparison between the quality of a music or physical education or art lesson given to even the youngest child by a specialist than one given by the generalist who is simply following some canned program.

But even when a school believes that specialization is highly desirable, the practical reality is that small schools will not be able to have specialists in everything that is being taught. And individual independent schools will not have evaluators who are specialist in each area of the program being offered. A solution may well lie in schools sharing resources. I have worked in small independent schools that have shared some teachers. If one school has a skilled evaluator with a background the sciences, and a nearby school one with a background in the humanities, why not have each do appropriate evaluations in the other school? There is also the possibility of contracting with external evaluators.

Not only does it require teachers with deep knowledge to offer really top-quality, “meritorious” and significant programs, those evaluating that work will be able to do so far more credibly and constructively when they bring sound, subject specific knowledge and experience to the task.